Research England, manager of the 2021 Research Excellence Framework (REF), argues that “the outputs of publicly funded research should be freely accessible and widely available”. When research is open access, it adds, it brings benefits beyond researchers, from students and institutions to governments, public bodies, professionals and practitioners, citizen scientists and many others.

Important questions follow from these statements that researchers should consider as they develop communication and engagement strategies for new projects:

- How can academics ensure that open access research brings benefits to wider constituencies, such as public bodies, professionals and others?

- What forms of open and engaging research communication would constitute effective sharing for wider constituencies?

- At what points in the research cycle should these communications take place?

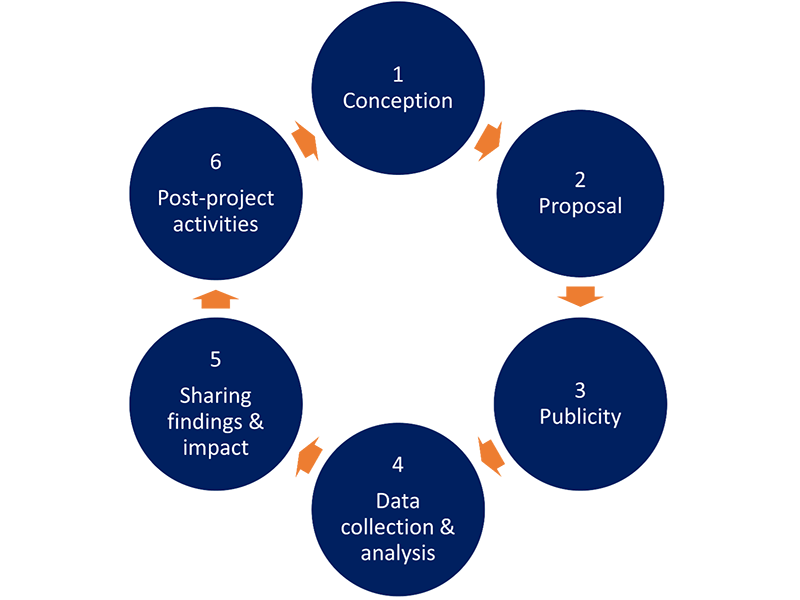

Thinking about the research cycle

At each of the six stages of the research cycle (see figure), those who plan research communication and engagement (that is, researchers and interested and affected parties) should consider:

- What information can and should be shared within the project team and, by extension, in the public sphere?

- What level of project or public communication will support the aims of the project?

- Is it reasonable or necessary to keep some (or all) information about the project confidential (for example, for commercial reasons)?

1. Conception

Effective communication at the conception of a new research project is essential. Initially, this could be relatively informal, through online or face-to-face meetings. It is important to capture the key issues raised in these initial discussions, and to share them with members of the proto-research team (including both researchers and wider constituencies) to confirm agreement about ways of working together. In order to achieve this, the first question is: who are the interested and affected parties for your research? (I am using “interested and affected parties” because of concerns about the term “stakeholder”.) This requires careful thought informed by a strategic approach. Issues of representation, and who could and should have a voice in an engaged research project, are key. What forms of expertise and experience could contribute in ways that improve the research process and/or contribute to positive outcomes? What are the needs of these interested and affected parties?

- How to succeed at policy engagement, part one: define your purpose

- Why learning to listen will help you avoid ‘helicopter research’ and make you a better science communicator

- Open research is a tough nut to crack. Here’s how we can get started

You could explore these questions through a horizon-scanning event; check the Sciencewise or Connected Communities websites for possible forms. The instigator could be you as a researcher or one or more interested and affected parties if they approach you.

2. Proposal

At this stage, agree on the aims of an engaged research project with interested and affected parties. A proposal for funding will codify agreements made during conception and proposal writing. This is likely to involve top-level decisions about who is involved, when and how (with the details to be agreed should the project be funded). The proposal stage is also the time to agree ways that contributions from interested and affected parties will be recognised. This could involve payment, but do not take this for granted; other measures may be more appropriate, such as co-authorship of outputs, acknowledgements or written recognition of contributions. Further, you should explore and agree in principle ways of sharing aspects of the research process, the findings and impact with interested and affected parties. What forms of communication will work for them? Would it be useful for interested and affected parties to be able to share aspects or the project proposal with their constituencies?

3. Publicity

Assuming that the proposal is funded, it could be useful to share what is planned with the interested and affected parties, and their constituencies. What form of communication of the project will work most effectively with them, noting that different groups could favour alternative approaches? (A policymaker could be looking for a research briefing offering different perspectives on an issue, whereas a community leader could require more detailed information about how they will be engaged and how their contributions will be used.) As an example, colleagues and I used participatory design with young people to identify ways to publicise a new school-university partnership. If you are looking to recruit further participation, what information is likely to be pertinent and in what forms?

4. Data collection and analysis

Forms of communication about data collection and analysis could include: minutes of meetings and agreed actions; “work in progress” presentations within the project team and at other events such as community meetings and conferences; and interim blog posts. Live data and associated analytical information could be shared with researchers, interested and affected parties and citizens through open notebooks, data visualisations, infographics, open coding/protocols or interim summaries.

In each case, the project team will need to consider what communications will support the project aims, be that forms of information giving (from researchers to wider constituencies), seeking (from wider constituencies to researchers) and/or sharing (between contributors to a project). Will you also need to organise events that generate consensus on an issue?

5. Sharing findings and impact

As the findings are agreed within the project team, refer back to the proposal, in particular to what was decided in terms of ways of sharing findings and impact with different constituencies. This is an opportunity to check again what forms of communication will work for different constituencies. Have new groups joined the project since it was funded? What forms of communication could work for them?

The project team should seek ways of publishing findings and impact in ways that are openly and easily accessible to those who could reasonably benefit from them (not just academics in their discipline). In a complex project with multiple constituencies, this is likely to involve various forms of communication, including peer-reviewed outputs. This could involve “grey literature” reports, research briefings, evidence cafes, blog posts, videos, podcasts, board games or comics.

6. Post-project activities

Connecting academics with wider constituencies in ways that are meaningful to all parties can be challenging when it comes to communication, but also incredibly rewarding. Do you and your project partners want to stay in touch? What ways could work for them and you? Could you develop a formal partnership?

Effective sharing is a core component of research and the outputs of publicly funded research should be freely accessible and widely available. A researcher’s conceptualisation of communication and engagement can and should involve a broader idea of effective sharing of new insights when interested and affected parties are involved. To be genuinely open and engaging, researchers should develop sophisticated research communication and engagement plans throughout the research cycle.

Richard Holliman is professor of engaged research in the Faculty of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics at The Open University, UK.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment