Providing feedback is a key component of the teaching experience as it assists in monitoring, guiding, correcting and encouraging students’ work. However, for some educators it can be a time-consuming, frustrating job, with a lack of student engagement and little recognition of the work that goes into writing individual comments.

Here, we explain a case study in which students were encouraged to actively give feedback to their peers and present an analysis of the type of feedback they gave. From reviewing the peer feedback, we found that this approach to evaluation can encourage student engagement and sense of belonging, and broaden the student experience.

Tackling the online engagement issue

As part of an online programme management (OPM) course for students who do not have a marketing background, Customer Centric Marketing is a foundation subject that is delivered 100 per cent online. It gives content, reading links, videos, exercises and assessment-related tasks on the Canvas platform, allowing both students and facilitator to provide examples, ideas and comments.

An issue for an online subject is how to get students engaged with the content and feel a sense of belonging. Undertaking an online course can be difficult for students, especially if it is on new subject matter or the student hasn’t studied for a long time. It can be isolating and lonely, resulting in students leaving the course.

- Guiding students to learn from each other through peer feedback

- Opinion: If peer feedback was good enough for the Brontë sisters, it’s good enough for us

- Assessment and feedback as an active dialogue between tutors and students

To encourage engagement, the students are asked to not only write their answers in a series of discrete tasks but also provide peer feedback on what their fellow students write, including on their main assessments.

While this was a relatively small class, with 18 students enrolled, peer evaluation provided a range of responses to the tasks, which greatly helped the facilitator in bonding with the students, the students when engaging with the content, and it supported bonding with each other.

Our analysis reviewed students’ comments during the subject. It looked at why students interact and types of feedback offered.

Reasons for student interaction

The aim of asking for peer feedback was to encourage engagement. We noted four main reasons why students were motivated to interact with each other online: altruism (students wanting to show care for others); networking (students being supportive of peers to find new friends or contacts); personal (students sharing personal opinion or professional experience); and to be seen (participating, knowing that they are being encouraged to engage by teaching staff).

Peer feedback categories

The peer feedback was grouped into five categories:

- connecting with peers

- cheering peers

- asking questions

- personal touch

- attention seeking.

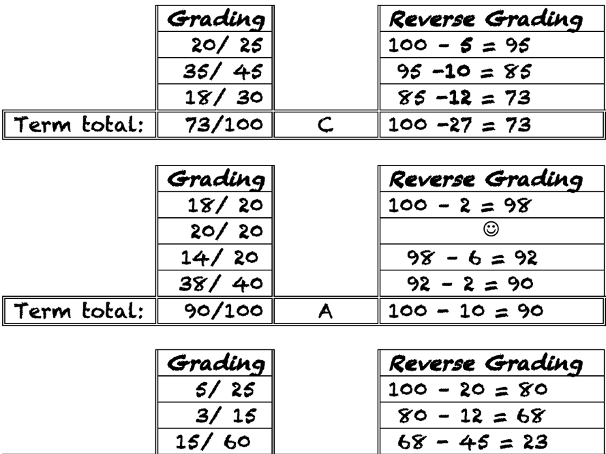

The table below includes examples for each feedback type.

Connecting with peers Based on name, pets, location or excitement: “Awesome Andrew*, nice meeting you :)”, “Love the name! I also go by Elly from some people. Go the Ellys! Nice meeting you :)”, “Hey Jane, So nice to meet you! Wow your work is interesting and also encouraging, I have often thought about moving to the country; it's good to know there are opportunities for marketing jobs in the country/regional areas” and “How is everyone going so far excited? 😁” |

Cheering peers Cheering each other on with encouragement: “Great analysis Elly!” and support – “Great insights about your company Mia!” |

Asking questions This was seen in clarifying questions: “Have other airlines responded to the pandemic? if so, why did you choose Qantas?” and questions prompting further discussion – “Do you have any insight on how the organisation plans to continue their growth and success post Covid?” |

Personal touch This was presented several times, including personally relating to the assessment case: “Interesting analysis for this segment! This sounds like it's being targeted towards me haha...”, “Hopefully, these insights help me to make a purchase for running shoes in the future; I love how well explained you write. Thank you for sharing this!”, “I will definitely try this!”, and “I hadn't heard of a situation with mislabelling products, that's so interesting!”. |

Attention seeking Saying things to get noticed/talk about themselves: “I live running but I have always used Asics…” |

After one discussion that received several comments, even the subject facilitator was impressed, saying: “Why do I get the impression you're all having a bit too much fun with this exercise!? 😄😄😄 Keep up the good work everyone.”

Observations from the peer feedback

After analysing the comments, we noticed features of the style of writing when students feed back peer to peer:

- Use of names: Students often included the name of the person to whom they were responding in their response, which added a personal and intimate tone to the comments.

- Casual tone: There was a level of informality in the students’ writing style (frequent grammar and spelling mistakes), which added to the authenticity of their responses.

- Encouraging words: There was frequent use of positive words such as “interesting” and “great” by students when responding to each other, and use of emotive terms too (for example, “love”, “like”, “blown away” and “insightful”).

Lessons for teaching staff

- Students with limited academic literacy levels or experience rarely participate in discussion boards with their peers, so they need more motivation to encourage confidence in responding online.

- The more active and engaged the online academic teacher, the more this attracts comments from students and a wider array of students to make public postings across the subject. So, online teaching staff should be regularly active with comments, ideas and messages of support.

- If the tone of the online academic’s communication is too formal, this reinforces a student-teacher dynamic and can reduce new student posts. Formal communication led to a limited number of students posting in response, so the teacher is encouraged to post and comment often and in a friendly, encouraging voice.

- The frequency of peer comments reduced over time (far more in Modules 1, 2 and 3 than in 4, 5 and 6), and the tone and nature of comments changed (less personal supportive, and more examples/experiences in later weeks as they worked through the content).

Reflecting on the subject where we actively encouraged peer feedback, we found that the students liked to feel they belonged. Reading each other’s posts, learning from each other’s industry experiences and receiving compliments on their own posts helped reinforce the group bonds.

The use of peer feedback was a success for this online subject, from our experience. While there was effort in making constant reminders to the students for comments and reviewing the student remarks, the students definitely appeared to enjoy the experience, which encouraged building an online learning community and a real sense of belonging.

As one student said: “I am blown away by the answers and constructive feedback.”

* Students’ names have been changed.

David Waller is associate professor and former head of the marketing department in UTS Business School; Kaye Chan is a senior lecturer in marketing and associate head (education) in the marketing department; and Melissa Clarke is a casual academic in the Business School, all at University of Technology Sydney.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment