As we all know, grades are far more than just letters and numbers to be placed in boxes – given that they represent the results of assessment, they are an essential part of the learning process. Unfortunately, the age-old dilemma of an F being the grade “given” by the instructor and an A being the grade that learners “got” results in distortion of what grading is and its role in the learning process for some students. And this can disorient their objectives and experiences at university.

To overcome this dilemma, I use a technique that allows learners to recognise the very clear connection between their academic performance and the evaluation of that performance. Best of all, at its core, the technique isn’t anything spectacular or groundbreaking. In fact, it relies heavily on standard good practice such as providing learners with clear instructions, directions and explanations on why each element of the assessment breakdown is there and how they reflect the objectives of the course. What I do differently is merely tweak when and how I “give” the learners their grades.

I introduce my ethos behind “reverse grading” at the beginning of the term as part of the regular introductions, and I find that learners usually pay great attention to the assessment breakdown. Perhaps this shouldn’t be surprising – after all, this is the part that defines the tasks they must carry out to complete the course.

- Assessment design that supports authentic learning (and discourages cheating)

- Equity, agency and transparency: Making assessment work better for students and academics

- Fear the zombie student apocalypse

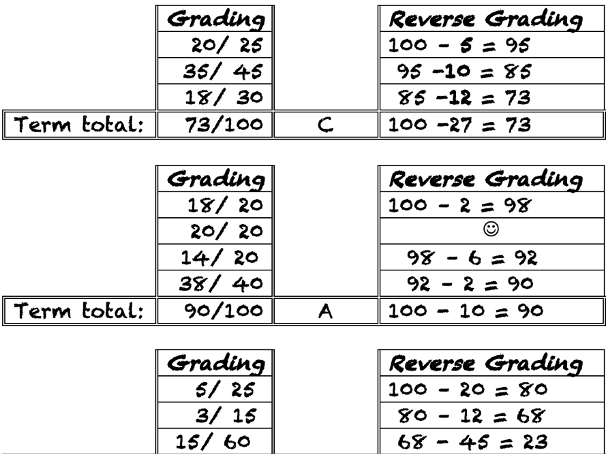

I explain that everyone enrolled on the course receives an A grade at the beginning of the term. As part of the course agreement, I commit to keeping them informed of whether any points from that A are likely to be deducted and what can be done to rectify this. In exchange, the learners are asked to acknowledge their responsibility to be actively involved in lectures and the attendant resources as a means of retaining the A they were “given”. As the instructor, I set the framework for assessment, but with reverse grading the learners are bound by our course agreement to be actively responsible for their own grade.

When I ask questions and invite learners to actively participate and respond, those who answer satisfactorily are given positive feedback and assurance that their points are safe, and for others I inform them which aspect of their answer or argument could be improved in order to better protect the points on their A grade. Of course, such clear and open feedback also helps the rest of the group.

Some learners find it hard to assess whether they are doing OK or not until it’s too late. If, indeed, I feel they could benefit from recognising that their performance is lagging, this is a good time to ask direct questions to those students. If their answers are unsatisfactory, I seize the chance to go over certain points and/or provide advice. They thus know that unless they follow the advice given and meet the requirements set for them, their grade will be subject to deductions.

This system can also be useful when wanting to set small assignments that carry no points towards grades. These should always come alongside clear information on how and why they will be useful for them later when they are working on their final project – when learners know that what they are doing will, in the long run, help them retain an A grade, it helps immensely with motivation.

The general idea behind reverse grading is for learners to receive the feedback and guidance they need while preparing their projects, to be able to assess how they are performing throughout the term rather than once it’s too late, to know what is lacking in their approach and, most importantly, how to rectify it and what to do differently for the A not to drop to a B or below.

When they are writing an essay, sitting an exam or putting the final version of their work into their portfolio, they can self-assess their performance against the criteria and instructions they were given. At the end of the term, they know that the final grade I enter on the system is not one I “gave” them, it is the one they “got” and is down to the points they themselves let go of.

As mentioned, reverse grading requires little more than the good, old practices of well-designed assessment methods and the ability to communicate these to the learners effectively. Additionally, it helps them recognise that an A is the grade we strive towards for them and that it is possible through engaging properly and realising that grades are earned rather than given – reverse grading provides a different narrative, one that brings everyone along on the journey.

Davita Günbay is a lecturer in the film-making and broadcasting department at Near East University in Nicosia, North Cyprus.

comment2

(No subject)

(No subject)