I remember encountering multiple choice questions (MCQs) as a student – I assumed that the instructor was neglecting their duties as an educator, by either outsourcing the assessment or opting for convenience in grading over effectiveness in learning. I remain instinctively sceptical about their use.

However, three things have changed recently. First, having taken several online courses, I have come to see their undisputed benefit for asynchronous learning. Second, I have noted their effectiveness within the classroom as an enjoyable way for students to check their learning and for me to monitor their progress. And third, the shift to online assessment removed the traditional, invigilated exam as an option. Now that we have better tools, more experience and weaker alternatives, it seems sensible to be open-minded.

- Designing assessments to support deeper learning

- Course learning outcomes: how to create them and align them to assessment

- Using technology to revolutionise the way you evaluate

The advantages of MCQs

MCQs offer advantages to students as well as instructors, including:

- They can be clearer, and less ambiguous, than open-ended questions

- They can cover a greater amount of course content than a reduced number of open-ended questions

- They remove discretion from marking and therefore generate greater consistency and transparency

- They automate grading and therefore eliminate human error.

Note that I do not include “reduces the time commitment of the instructor” on the list above because although MCQs are quicker to grade, their construction and implementation is more burdensome than traditional exam questions. Thus MCQs benefit instructors who are comfortable shifting labour from marking exams to designing them.

The suitability of MCQs

I split my assessment questions into three categories (building on the work of American psychologist J. P. Guilford):

Command questions: these test convergent thinking, in that students are intended to arrive at the same answer as each other. The solutions should be unambiguous and objectively assessed. Different instructors should be expected to give identical grades. Verbs for convergent thinking include: choose, select, identify, calculate, estimate and label.

Discussion questions: these test divergent thinking, in that students are expected to provide original answers. What constitutes a good answer can be communicated via a mark scheme, but there is significant scope for students to deviate from each other in their work. Verbs for divergent thinking include: create, write and present.

Exhibit questions: this can be either a command- or a discussion-style question, but the students provide their solution in the form of a visual image. For example, students must create a graph or complete a worksheet.

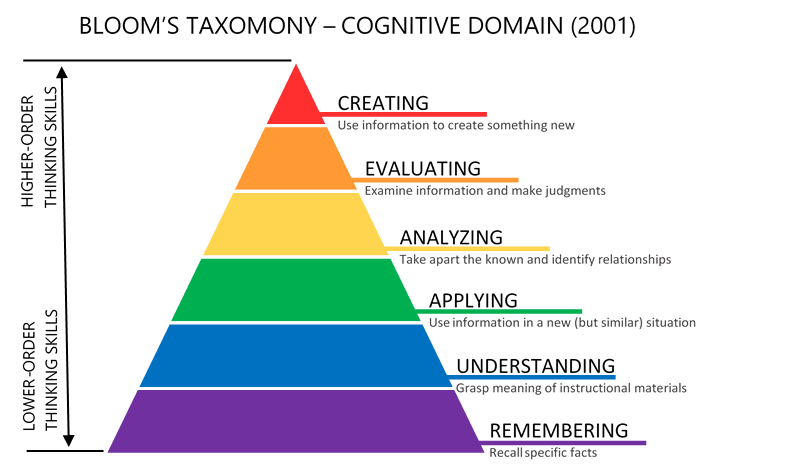

In terms of Bloom’s taxonomy of learning, the top two levels, namely creating and evaluating, broadly relate to discussion questions, and the bottom two, understanding and remembering, are more suitable for command questions. I believe that when constructed well, MCQs can also occupy the middle two, which are analysing and applying. But this isn’t a necessary condition for their usefulness.

Provided that other assessment methods are used to verify higher order thinking, this article explores the use of MCQs in their proper domain.

The structure of MCQs

A well-composed MCQ has two elements:

1) The stem – this is the “question” and should provide a problem or situation.

2) The alternatives – a list of options for students to select, containing a correct answer and several distractors.

Some best practice principles include:

The stem should be succinct and meaningful – it should contain only relevant information and focus attention on the learning objective without testing reading skills. It should be meaningful when read in isolation, and it should seek to provide a direct test of students’ understanding, rather than inviting a vague consideration of a topic.

Material should relate to course content – questions must find a balance in being related to the course content but not being a trivial memory test. If the question relates to a simple definition, or anything that can be googled, it calls into question the value of the course. Or, if the instructor is using a bank of questions from a textbook, perhaps students should just study the textbook directly. Having a set of questions that are general and widely used creates an unfair advantage to students with prior background knowledge. Questions should include some nuance while relating to what has been taught, to detect if students were actively engaged. For example, there is a difference between asking “which of the following are stakeholders” and “which, according to the lectures, should be considered as stakeholders”.

Consider the Texas two-step of higher level assessment – as instructional designer Mike Dickinson explains, this is a way to increase the capability of MCQs by introducing higher-level thinking. The idea is that although students can’t “describe” a concept if they have pre-assigned alternatives, they can “select the best description”. MCQs don’t allow them to make an interpretation, but they can “identify the most accurate interpretation”. Think about what you want the students to do and what the associated verb would be, ie, describe or evaluate, then change this to its noun form, ie, description or evaluation when writing the MCQ.

Avoid negative phrasing – providing a list of options and asking which is not correct adds a layer of complexity and thus difficulty, but especially for non-native English speakers, it can move the focus towards reading comprehension rather than subject comprehension. If negative phrasing is necessary, using italics to draw emphasis is sensible, for instance, “which of the following statements is false:”

Avoid initial or interior blanks – requiring students to fill in missing words moves the cognitive load away from a mastery of subject-specific knowledge. In many cases, stems can be rewritten to retain the purpose of the question.

All alternatives should be plausible – there is nothing wrong with using distractors as bait. Instead of listing a correct answer and several random words, each distractor should be considered. Brame argues that “common student errors provide the best source of distractors” and as long as they are genuine errors, and not evidence of poorly worded questions, this is true. If I ask “which of the following, according to the course material, is an element of justice? a) Power; b) Reciprocity; c) Respect; d) Equity” a student who selects “c) Respect” may be frustrated if they don’t get a point and cite multiple internet articles arguing that the concept of respect is relevant to understanding justice. As indeed it is. But in my class, we use a framework that looks at four elements of justice, one of which is b) Reciprocity, and none of which is c) Respect. The fact that one can make a plausible argument for why respect is an important element of what constitutes justice is what makes it a good distractor.

Alternatives should be reasonably homogeneous – having wildly different options can serve as clues about the correct answer, so the alternatives provided should be reasonably similar in language, form and length. Astute and savvy students shouldn’t be advantaged over more naive students.

Don’t always make B the correct answer – whenever I create MCQs, I remember a former student who “revealed” his strategy of always choosing option B. Given that he was on a postgraduate course, this strategy must have proved successful.

Be careful with using “all of the above” or “none of the above” as options – these aren’t considered best practice because they allow students with partial knowledge to deduce the correct answers. However, when used deliberately, they can prompt a closer engagement with the question by forcing students to read it several times. This is especially true with alternatives such as “a) A and B; b) B and C; c) none of the above; d) all of the above”.

Vary the number of distractors — providing four options throughout implies that random guessing is worth 25 per cent of the exam. Offering more distractors therefore forces students to confront each one and select something. Presented with more options, students are more likely to try to answer the question themselves, and then see if their answer is listed, as opposed to reverse-engineering each option, to see if it’s correct. However, too many options make it harder to maintain plausibility and homogeneity. Therefore varying distractors, from 2 to 5 depending on the question, is totally appropriate.

Anthony J. Evans is a professor of economics at ESCP Business School.

This advice is based on his blog, “Creating good multiple-choice question exams”.

comment