Let’s say you’re an English academic. English literature. A medievalist. And at very late notice you’ve been asked to run a workshop for a creative writing colleague who has just won a literary prize and needs to go and collect it, in Bremen. Or has just tested positive for Covid. You have three hours to prepare. This is for you.

As part of my PGCE training, I did a teaching observation on a class taught by a fellow academic, and she did the same for me. Her class was on the history of art. It was a conventional lecture with PowerPoint. Bullet points, questions at the end. My class was a conventional creative writing workshop. Student stories submitted, discussed.

After her students all filed out, the first thing I said to her was: “That was so interesting. I learned a lot.”

After my students had all filed out, the first thing she said to me was: “That isn’t teaching, it’s more like…ego-management.”

She was right.

Ego management is a perfect description; and a lot of how a creative writing workshop works or doesn’t work depends on the students’ respect or lack of respect for the tutor. If the tutor has published lots of books, or a few successful books, they will get respect – for the first few minutes, anyway. The students will assume this person is worth listening to, because they’ve fulfilled the students’ ambition: to be known as a writer.

If you don’t have this publication record (prizes help, too), then you will have to earn the workshop’s respect another way.

Over the course of a few weeks, you can gain respect just by being a good, attentive tutor, as you are in an English seminar. Within two or three workshops, you can do this by managing their individual egos amusingly or tactfully. But if you haven’t got that much time – if you just have to walk into the classroom and start running a discussion on their short stories – then you’ll have to be more direct.

- Spotlight: Write here, right now

- Creating bridges to academic writing for first-year university students

- Don’t jettison traditional academic writing just yet

Most of all you can earn the respect of the workshop group by having read more than they have, and by putting that lifetime’s reading immediately and practically to their use. You and your knowledge are there for them, and you’re starting from where they start. Today, on this page, in this sentence. This might seem obvious, but it’s often not how literature is taught.

It’s likely that where you usually start is, say, the Penguin edition of Margery Kempe rather than, say, an Epic Tale of Sword and Sorcery featuring Ninja Squirrels Who Can Fly.

What students particularly respond to is your knowledge and love of the genre they themselves are writing. And if that doesn’t yet include Ninja squirrels, it does (because you’re a medievalist) include dream visions, battles between good and evil, fantasies of flight and basic story structures.

If you know where a student’s coming from – that they adore Sally Rooney or W. G. Sebald or Neil Gaiman – and you display knowledge of and respect for that writer, you will go up in that student’s estimation. Even if they don’t immediately take to you personally, they will feel reassured that you’re not lazily misreading or showing disdain for them or their work.

Because of this, it is absolutely essential that you never slag off any published writers when speaking in a workshop. Quite possibly, one of these “bad” writers was what got a student into reading in the first place.

Among the first long books I ever read were Jeffrey Archer’s Kane and Abel and R. F. Delderfield’s Diana. In both cases, I enjoyed them and was proud of myself for finishing so many pages. If an authority figure had sneered at them, and by implication sneered at me for liking them, and done this in front of other people, I might have been done with reading forever.

With every writer that is mentioned in the workshop, you should focus on what they are good at and what can be learned from them. Archer is very skilled at getting the reader to keep turning the pages by use of big, catchy, high-stakes plots. Delderfield makes the reader care a great deal about the emotional life of the main character. How? Well, let’s look at how you’re doing it in your story…

No one ever became a better writer by sneering at other writers.

I’d suggest that the best view to take, in or out of a workshop, is that there’s no such thing as bad writing, only inappropriate or misplaced writing.

So when you start the discussion about a student’s story, ask the group what they thought it was doing right. What is already working? Then someone will say “but…” and you can take it from there. Don’t let the first student who speaks turn the tenor of the conversation to criticism.

Before the workshop, you should closely read each story, so as to identify at least three things to praise. Some neat characterisation here, some real emotional depth there or, as a last resort, the pacing and energy. Just as with written feedback, a workshop discussion of a story should be a sandwich. Begin and end with enough praise to help the student assimilate the critique in between.

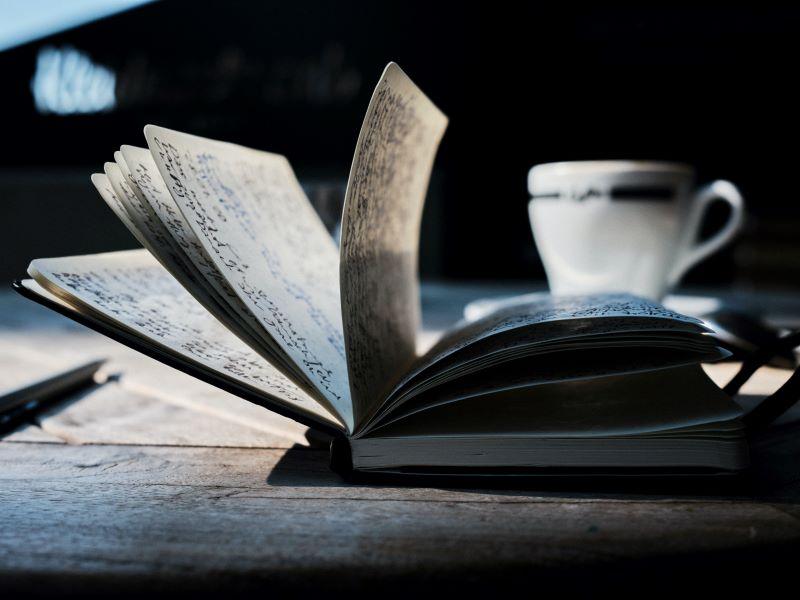

Toby Litt is an associate professor of creative writing at the University of Southampton. His latest book is A Writer’s Diary (Gallery Beggar Press, 2023).

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment