What if students don’t handle meetings with external stakeholders well?

Picture this: a student is given the opportunity to meet with industry clients to tackle a real-life challenge. But what if they don’t handle the meeting well? As educators, it is our job to prepare students for these types of situations. We often provide templates or guidelines, but we can’t ensure they’re being used effectively, or even at all. And let’s face it, students don’t know what they don’t know until they have the experience. Well-prepared students can make a huge contribution to companies and gain valuable professional skills and attributes in the process. However, when things go wrong, it can damage the reputation of the course and the university, not to mention the student’s confidence. So, what can we do to avoid this?

Avoiding client contact in a professional course is not an option

One way to mitigate this risk is to design the course so that student contact with the outside world is minimal by using case studies or simulations. But this limits students’ development. A more realistic choice is to scaffold students’ preparation for the client meeting by employing an active feedback approach where students generate their own feedback on their client meeting plan even before the meeting takes place. The first meeting sets the stage for all other student-client interactions and the success of a project, so it is important that both parties get as much from it as possible.

- Resource collection: Putting feedback at the heart of assessment

- Guiding learning by activating students’ inner feedback

- Why students are best placed to help students understand feedback

The active feedback approach

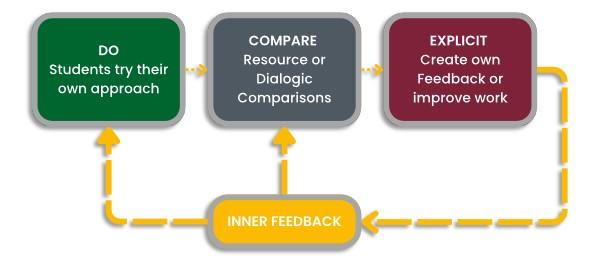

The active feedback approach works like this:

- Students DO or CREATE something; their own approach to a challenge or a task.

- Then they COMPARE their work or performance against another resource or resources.

- Then they produce EXPLICIT outputs, for example, write self-feedback comments or make improvements to the original work.

Resources might be documents or videos or anything that contains relevant information, or they can be comments from other students, clients or teachers written or provided during a dialogue. Active feedback can enhance student learning in the classroom, particularly in experiential settings where students are challenged to create and apply their knowledge to real-world scenarios.

How do you apply the active feedback approach to the client meeting?

Students are given a short client brief which highlights the challenge that the client is facing. They are then asked to create a plan for the first client meeting (DO) which should enable them to clarify the client’s expectations and deliverables for the consultancy project and to create resonance with the client themselves. Students can create a plan as a flow chart, diagram, table, script or even a cartoon. No template is provided by the teaching team. Students are given different comparators one after the other so that they build continuously on their original plan by creating their own feedback. This iterative approach uses a number of resources and dialogues:

- Article comparisons: Students compare their plan with a short excerpt from an article that describes how professional consultants meet with clients and how they establish credibility and resonance. After this they update their plan.

- Peer comments comparison: Students then meet with their team and are asked to discuss their own individual plans and create a single team plan. Again, students are asked to update their own individual plans following this comparison.

- Video doctor-patient discussion comparison: Students then listen to a video of a student doctor conducting an appointment with a person presenting with chest pains and students are asked to compare their meeting plan to the video and to make any improvements.

- Mentor feedback comparison: The teams then present their meeting plans to their expert mentor and make any improvements following the discussion.

- Client meeting comparison: The last step is the client meeting itself and students are asked to reflect on how the meeting went and how effective their plan was and to make any subsequent improvements such that they could use the plan in the future.

Key features and implications

Key benefits of this approach are that different comparators lead to different kinds of feedback. For example, the video with the doctor helps students understand the importance of collecting relevant information before attempting to provide a diagnosis, which is the purpose of the consultancy project itself rather than the first meeting. Both human and material comparisons are used so feedback is not just generated from comments. None of the comparators are exactly like what students produce so no exemplars are used.

This approach:

- Minimises teacher workload. Rather than supplying individual feedback throughout, teachers give resources and provide instructions to scaffold. Students create their own feedback.

- Students retain agency over the entire process. Creativity is also challenged and enhanced.

It is important to explain the active feedback process to the students, that this is an authentic feedback phenomenon that builds on an entirely natural metacognitive process which mimics how feedback happens in professional practice. For example, when an employee is asked to write a report for the first time, they may compare their own effort with previous examples or a dialogue with a senior colleague before submitting it.

Preparing students for client meetings and interactions is crucial in professional courses, but it can also be a source of anxiety for students and teachers. While avoiding client contact altogether is an easy solution, it limits students’ development and does not prepare them for the real world. The active feedback approach offers a powerful tool to enhance student learning in experiential settings while minimising the risk of reputation damage for universities. So, go ahead and try out this approach and see the difference it can make.

Nick Quinn is associate director of connections with practice and Alison Gibb is associate director of learning and teaching at the Adam Smith Business School, University of Glasgow.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment