“How come you’re not working?” asks Bill Hicks’ boss. “There’s nothing to do,” replies Bill. “Well,” says the boss, “pretend like you’re working.”

Some now talk of the “great resignation”, that an exodus of professionals is looming. Is it a “First World problem”, perhaps due to automation or loss of confidence in our way of life that means − having eliminated physical and then intellectual labour − much of what we now do is emotional, psychological labour? Why do we absorb stress and humiliation in rituals of make-work administration invented to justify hourly pay?

One medicine that would heal so much, and restore productivity, is that we learn to have fun again. Hicks reminded us that “it’s just a ride”. In 2020, I fell off my ride. The lecture theatre, where I’d talk authoritatively for hours in a caffeinated frenzy, was suddenly empty. With a bump, we all landed on a new ride. This consisted of sitting at home, playing a computer simulation, pretending that we were still on the old ride.

The subject of this piece is play and its close relation to risk. It’s how children learn. It’s also how adults manage novel situations, spur innovation and successfully steer businesses through new challenges.

Psychologist Jean Piaget used schemas to explain how we think, while Roger Schank and Robert Abelson used the similar idea of scripts. Life gets interesting when scripts fail, the game changes and two key responses, fear and curiosity, kick in.

For some, dissolving norms and expectations is terrifying. For others, exhilarating. In play, as in war, a new time frame emerges. Getting through the next 10 seconds is the big plan, anything can change, everything is negotiable. We are more open to deep change and tend to learn quickly.

- Let’s play! Using games to teach statistics and economics

- How play can engage students and deepen learning

- Resources for fostering creativity in higher education

Presently, another game changed for me. My daughter, who had left the house each morning to be taught by professionals, stayed home. Her world, much richer and more fluid, comprising dragons, dinosaurs, kittens, Anna and Elsa, spilled helter-skelter into my orderly study, along with her catchphrase: “Daddy, let’s pretend.”

As life went off script, rather than clinging to professionalism and compartmentalisation, I let fear and curiosity into the room. Unsurprisingly, my fantasy of videoconferencing a big class, expertly fielding students’ questions while my little girl sat patiently doing maths, didn’t happen. A fight soon erupted between dragons and kittens, so Daddy’s help was needed. And so it goes.

Had I stuck rigidly to my unreasonable script, it would have been a lose-lose prospect. Chasing her out of the room, or becoming a nagging dad, failing to multitask, would mean letting down child and students alike. This is where the important element of risk comes into play – and it’s relevant to universities, too, some of which wrongly choose to use systems such as Microsoft Teams because they can monitor and record classes. This is creepy, unnecessary and damaging because it is inhibiting.

Had a less-secure tool such as Teams or Zoom been the only available option, I might have worried about what others thought, and with half a mind on student complaints or management disapproval I might have frozen. Fortunately, we use an alternative videoconferencing software called jit.si, which is secured against snooping, and what happens in end-to-end encrypted sessions, stays in end-to-end encrypted sessions.

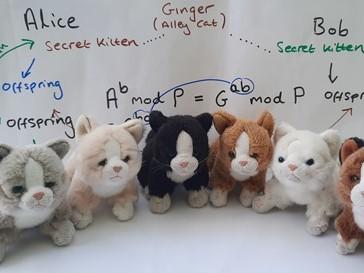

“Let’s pretend that Ginger is going to scratch them,” said a little voice, my daughter pulling herself on to my chair. Explaining Diffie-Hellman key exchange is a tricky task. “Let’s pretend Ginger is a randomly chosen large integer,” I suggested. My daughter nodded in agreement. It turns out that, with a little imaginative play, different-coloured kittens make a fine way to teach cryptography students of all ages.

Playfulness is applauded by the great educators including John Taylor-Gatto and Sir Ken Robinson, who spent their lives fighting humdrum drudgery in our schools. But play is largely absent from HE, even though students of all ages benefit from it. Anyone in my classes can take a pseudonym or silly avatar. Email or private messages remain as “official” connections.

I’m unsure whether anyone has made a serious study of academic games, in the vein of Eric Berne’s Games People Play, but adults are generally preoccupied with different games related to interpersonal power. Universities are run by what spiritual sociologist Alan Watts dubbed prickly types, less able to understand fluid situations where playful resilience shines. It’s hard for them to let go of trying to control everything and always be right, and instead try testing silly ideas, pushing boundaries, abandoning fixed identities and speaking without fear.

Throughout the homeschooling year, I lost many boundaries between my world as a university professor and my new life as a primary school teacher (for whom I have a newfound respect). It has shaped my adult teaching for the better. Things I’ve learned include embracing fallibility, dealing with shorter attention spans and random comings and goings, celebrating the absurd and letting go of control.

But one cannot relinquish control one does not have. Teachers must have control over their choices of tools and methods. Lockstep IT policies, however well meaning, are an obstacle to good practice; freedom-enabling, open-source software that respects individual choice and privacy is better suited to the job.

Although we regularly pay lip service to progressive teaching, I don’t think we have the courage to “play” for real. Genuine play doesn’t occur under dystopian surveillance conditions or the bureaucratic micromanagement rife in our institutions. Sadly, by allowing a culture of control and monitoring to flourish in universities, we inhibit a vital factor in learning.

Andy Farnell is a British computer scientist specialising in signals and systems. He is a prolific speaker, visiting professor, consultant, ethical hacker, author and lifelong advocate for digital rights. He is teaching cybersecurity while writing a new book, Ethics for Hackers.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment